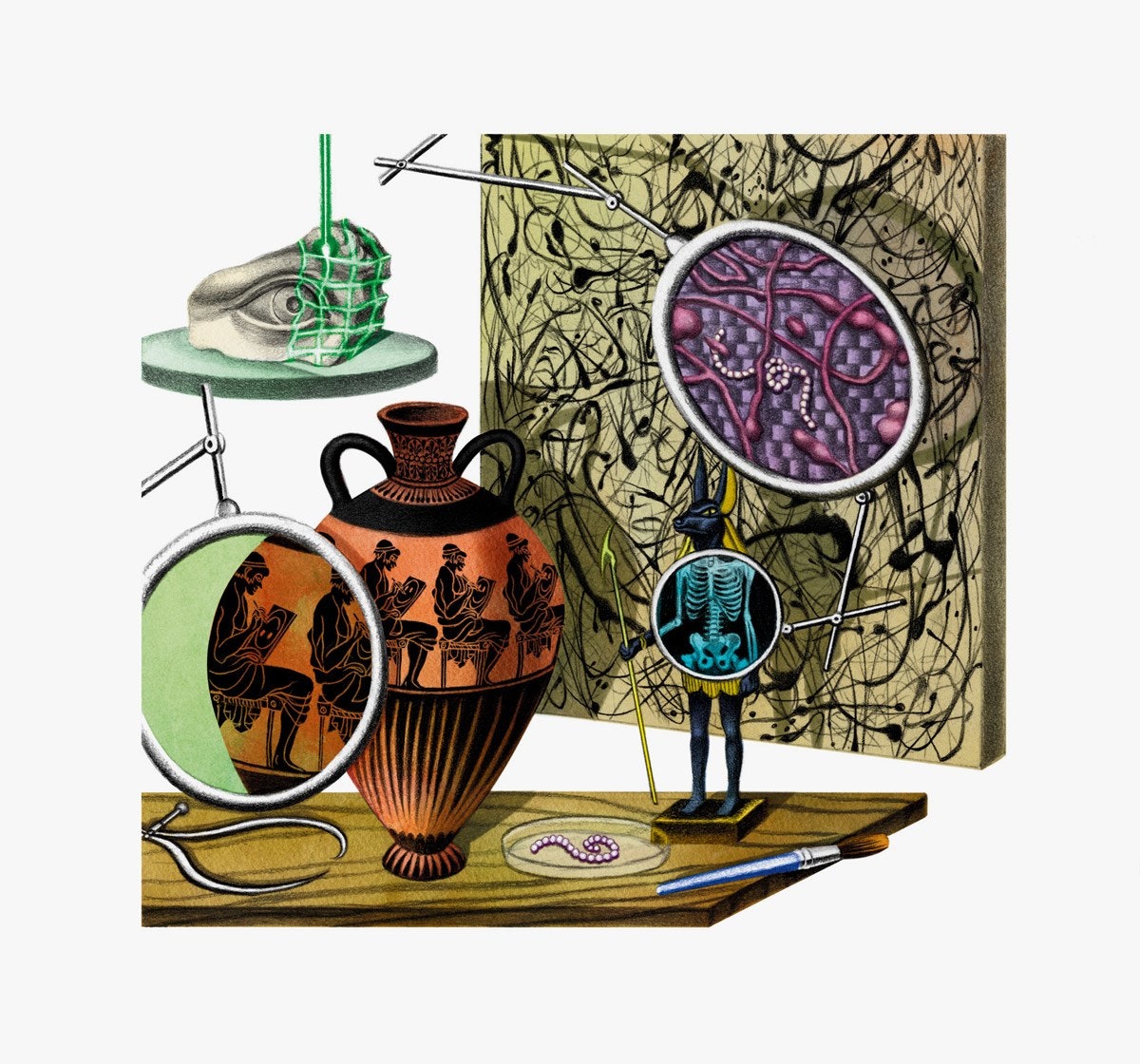

What is an alleged crime title that comes across as sophisticated and esoteric? The answer is art forgery. Why? Because not only does the delinquent executing the job need a consummate level of artistry and familiarity with the original artist, but they also must have historical expertise specifically pertaining to art movements, technological advances, and a strong knowledge of chemistry To pull off a sham, the counterfeit must resemble the original not just in appearance, but also in materials; the artist must employ the appropriate materials and pigments with correct dating to establish authenticity. One technique to detect falsified works is Raman spectroscopy.

Raman spectroscopy is a non-destructive chemical analysis technique that uses light scattering to identify a molecule’s “unique fingerprint;” Non-destructive means conducting material analysis without damaging the samples. To understand a molecule’s “fingerprint,” one first needs to know the difference between non-synthetic and synthetic pigments and their role in identifying the piece’s age. Non-synthetic pigments are made from natural origins such as minerals, plants, insects, and are not chemically modified. However, they can be physically processed such as being washed and sifted. Synthetic pigments are carbon-based molecules manufactured from chemicals such as petroleum, acids, and are chemically modified. The technique for producing synthetic pigment on an industrial scale began circa 1860. For this reason, when a painting is supposedly from the late 17th century but synthetic pigments are detected, it is an obvious fake.

Most non-synthetic pigments are obtained from minerals that usually have a crystalline structure. Crystalline solids interact with light and create a unique scatter pattern, like a fingerprint, revealing its chemical structure, phase, polymorphy (form and crystal structure), crystallinity, and molecular interactions. This permits the identification of the name of the pigment and its ingredients. Scientists that establish the authenticity of works of art (Jennifer Mass, an American chemist and materials engineer working as an art investigator), possess an archive of spectral structures of countless pigments, dyes, binding media, fillers, and driers all identified to pertain to a specific artist or period, like the 17th Century artists or the modern expressionists of the 1910s. By applying Raman spectroscopy to a subject of forgery suspicion, Mass can compare the identified ingredients with her library of data and thus easily confirm its authenticity.

The advantage of Raman spectroscopy lies in its aptitude to analyze samples of size ranging from milligram to kilogram, as well as its impregnability to water interference, thus allowing the examination of aqueous specimens (a reason for its high acclaim in not just the art field, but also the archeological field). With the constant upgrade in Raman spectrometers, the time to produce Raman maps of a specimen will shrink to 1 millisecond and below, therefore forensic artists can expect a prospect with faster triumphs. More and more museums are installing Raman devices. Who knows? Maybe Raman will become the Kryptonite to art crimes.