The year is 1818. Napoleon’s defeat has ended the First French Empire for good, and colonialist tendencies are spreading unchecked across the globe. Industrialisation has led to massive scientific and commercial discoveries, while provoking considerable mistrust in working-class populations.

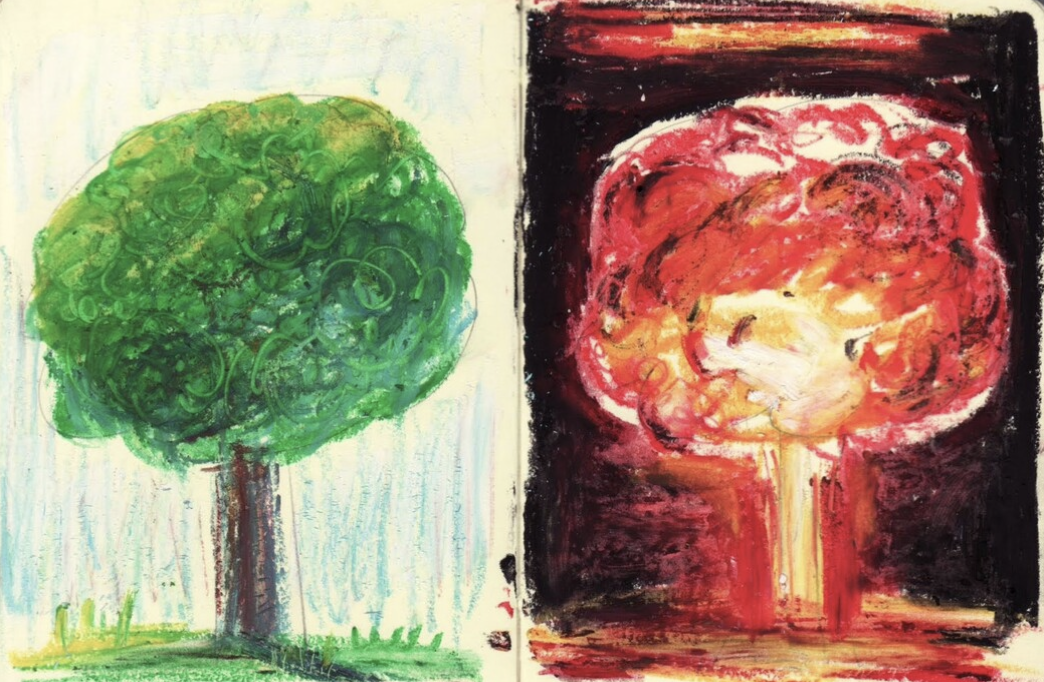

Literature is experiencing a golden age brought about by the publication of works by authors including Lord Byron and Jane Austen. And perhaps the most pressing event of all: Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley, has just been published. While the book’s release marked the beginning of contemporary science fiction, the questions it raised had plagued scientific discovery for centuries. How do scientists know when to stop? What happens when experiments get ‘out of hand’? And if science is about achieving the impossible, about pushing boundaries…what happens when those boundaries snap?

Ethics has been the subject of debate in the scientific and biomedical community almost since their conception. Ethics hold particular importance when “traditional customs or behaviours are challenged by new developments” (NLM). Although contemporary principles are largely drawn from Christian teachings, scientific progress in the Western world was discouraged by religious entities until very recently. After the Enlightenment renewed interest in the natural world, codes of conduct drafted centuries ago were rediscovered.

The principles which modern doctors are held to nowadays draw inspiration from these ancient documents and scriptures. The most famous of these is the Hippocratic Oath, a document more than two millennia old which emphasises two central tenets of medicine: help the ill and prioritise patient care above all else (Northeastern University).

During the latter part of the 20th century, the most popular ethics concerns centred around the application of science in creating new weapons like the nuclear bomb. But another problem had been brewing in the medical field for decades, summarised in two words: clinical trials.

The idea of testing medications or procedures on humans is not a new one. The first recorded ‘clinical trial’ is found in the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament, written half a millennia before the birth of Christ. Even so, cures before the nineteenth century were largely experimental, if beneficial to the patient at all. By the Victorian Era, however, the clinical trial was recognised as the “golden standard and most dominant form of clinical research”. Advancements such as placebo drugs, randomised selection and double-blind trials all helped increase the validity of these scientific experiments. The publication of established guidelines, as demonstrated in the book Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, and rules used by organisations like the Medical Research Council further gave credibility to the use of the clinical trial as a safe and effective means to advance medical knowledge. As a result, “over several hundred years, the scientific aspects of conducting clinical trials and the associated medical advances continued to improve at a seemingly exponential rate, especially in the early 1900s” (Marshall University).

Yet despite all of these measures, the biggest medical scandals of the past century have been clinical trials whose incredible risks and irreversible consequences have demonstrated the true dangers of unethical science.

The Thalidomide Scandal, in which the titular sedative caused severe malformations in more than 10,000 children during the 1960s, passed unchecked throughout clinical trials as researchers neglected to investigate the drug’s effects on pregnancy (ListVerse). The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which ran from the 1930-1970s, denied hundreds of Black men treatment for syphilis that led to many of their deaths and the infection of their wives and children, all in order to investigate the effects of untreated syphilis on their bodies (CDC).

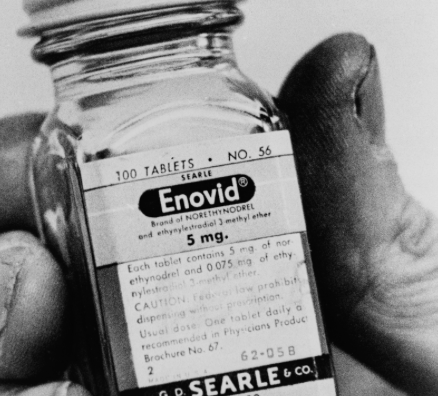

And the birth control pill was first tested in incredibly high dosages on Puerto Rican women living in poverty, inciting severe side effects in some and killing others (History). Some of the research from these experiments has proved to be invaluable in recent decades, but the studies’ disregard for their subjects caused worldwide shock and suffering. Clinical trials are modern medicine’s ‘experimental Frankenstein’; they can either go very, very well – or very, very wrong.

Not only do clinical trials pose grave risks to their subjects when conducted unethically, their results can be manipulated in ways that support dangerous theories. Eugenics, a movement that gained traction at the beginning of the 20th century, encouraged the ‘perfection’ of the human race through the elimination of social ills. Even in developed countries, this led to the sterilisation of tens of thousands of people who were labelled ‘undesirables’ up until half a century ago. Eugenics movements were also heavily linked to racist and xenophobic attitudes which emphasised the racial and cultural supremacy of Western populations (Genome). With the rise of genetic sequencing methods and technology like CRISPR, there is newfound concern that this science could produce horrific circumstances. Reckless projects such as the (failed) genetic engineering of twins by Chinese scientists in 2015 have done little to quell these fears (Popular Mechanics). These dystopian scenarios we see reflected in popular culture occur when scientists take it in their own hands to act based on data which may or may not be reliable. How that data is acquired, and what they do with it, can have international repercussions.

All biomedical discoveries hold the potential for massive good. The power to influence a person’s health is one of the greatest achievements of past centuries, but history serves as a reminder of the atrocities that occur when science is placed in the wrong hands. The Holocaust serves as an extreme example, but the immense suffering inflicted by cruel ‘scientists’ who refused to recognise the humanity of their subjects is a lesson that cannot be forgotten.

The infamous experiments conducted by Joseph Mengele (the ‘Angel of Death’) and thousands of other medical professionals demonstrate just how vital it is that clinical trials remain subject to the ethical regulations applied to all medicine. And while the Nuremberg Code, established in 1947, was created to prevent similar atrocities from ever happening, science hasn’t stopped advancing since then (USHMM). The responsibility to help humanity through science must never be forgotten, or the unimaginable is risked.

“Beware; for I am fearless, and therefore powerful” (Shelley). These words that Shelley imagined Frankenstein might say more than two centuries ago continue to carry weight. They serve as a reminder of the ethical responsibilities that all scientists must carry when exercising their duties. They also bear witness to the inconceivable cruelty that knowledge poses when handled incorrectly. And more than anything, they hint at the oath that every scientist should be required to take: that, as Nobel Laureate Francoise Barré-Sinoussi stated, “we are not making science for science. We are making science for the benefit of humanity” (Barré-Sinoussi). Only then will Frankenstein remain a figment of our imagination. And only then can the nightmares be kept in our books and out of our lives.

Bibliography:

Blakemore, Erin. “The First Birth Control Pill Used Puerto Rican Women as Guinea Pigs.” HISTORY, 11 Mar. 2019, www.history.com/news/birth-control-pill-history-puerto-rico-enovid.

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. “The Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee Timeline.” Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, 5 Dec. 2022, www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

Iaccarino, Maurizio. “Science and Ethics.” EMBO Reports, vol. 2, no. 9, 15 Sept. 2001, pp. 747–750, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1084045/, https://doi.org/10.1093/embo-reports/kve191.

Little, Becky. “Delivering “the Pill” Wasn’t Easy.” Adventure, 18 Dec. 2014, www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/141218-birth-control-pill-contraception-science-medicine-ngbooktalk.

McPherson, Laura. “The History of the Hippocratic Oath.” Northeastern ABSN, 8 May 2019, www.absn.northeastern.edu/blog/the-history-of-the-hippocratic-oath/.

National Human Genome Research Institute. “Eugenics and Scientific Racism.” Genome, National Human Genome Research Institute, 18 May 2022, www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Eugenics-and-Scientific-Racism.

Nellhaus, Emma M., and Todd H. Davies. “Evolution of Clinical Trials throughout History.” Marshall Journal of Medicine, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 2017, https://doi.org/10.18590/mjm.2017.vol3.iss1.9.

Newcomb, Tim. “The First Gene-Edited Babies Are Supposedly Alive and Well, Says Guy Who Edited Them.” Popular Mechanics, 7 Feb. 2023, www.popularmechanics.com/science/health/a42790400/crispr-babies-where-are-they-now-first-gene-edited-children/.

Pineda, Julett. “Life and Ethics in an “Era of Genetics” – DW – 07/27/2022.” DW, 27 July 2022, www.dw.com/en/life-and-ethics-in-an-era-of-genetics/a-62617465.

Sauer, Sydney. “Top 10 Clinical Trials That Went Horribly Wrong – Listverse.” Listverse, 19 June 2017, listverse.com/2017/06/19/top-10-clinical-trials-that-went-horribly-wrong/.United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Nazi Medical Experiments.” USHMM, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, 30 Aug. 2006, www.encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-medical-experiments.

Such a great article Natalia! Was captivated from the first lines… I love your use of Frankenstein, foreshadowing the ethical (ir)responsibilities present in past clinical trials and thinking through the ways in which scientist may find ways to be more responsible with their expertise… lots of relevant TOK material in here! Thanks for sharing 🙂