In 2015, famed entrepreneur and philanthropist Bill Gates gave a TED Talk titled: “The Next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready”. Gates detailed how, in the face of the massive progress that humankind has made in the past few centuries, the greatest threat we face nowadays comes not from war or traditional conflict, but from disease (TEDx). Following the COVID-19 pandemic, which spread halfway across the globe before governments could catch their breath, many questioned whether Gates had ‘seen ahead’ and predicted the future. But did COVID-19 and the havoc it wrought represent the pathogen that could, for good, end our legacy? Are we still waiting for Gates to be proven right, or is it only a matter of time before the next outbreak becomes humankind’s last?

From an evolutionary perspective, species that ‘outgrow’ their environments are subject to a series of mechanisms that prevent their population from becoming too successful. As a population rapidly increases, they start to become a burden on their environment. Because ecosystems have limited resources, they have set ‘carrying capacities’ past which a species’ size is no longer sustainable. As a result, two main strategies are used to restore balance to the ecosystems they inhabit. The first, predation, is unlikely to represent a threat to human survival.

But the second, and arguably deadlier, strategy of disease has the possibility to not just significantly reduce the human population, but eliminate it altogether. After all, predators are subject to the same environmental constraints as their prey. On the other hand, once an epidemic begins it can have truly devastating consequences.

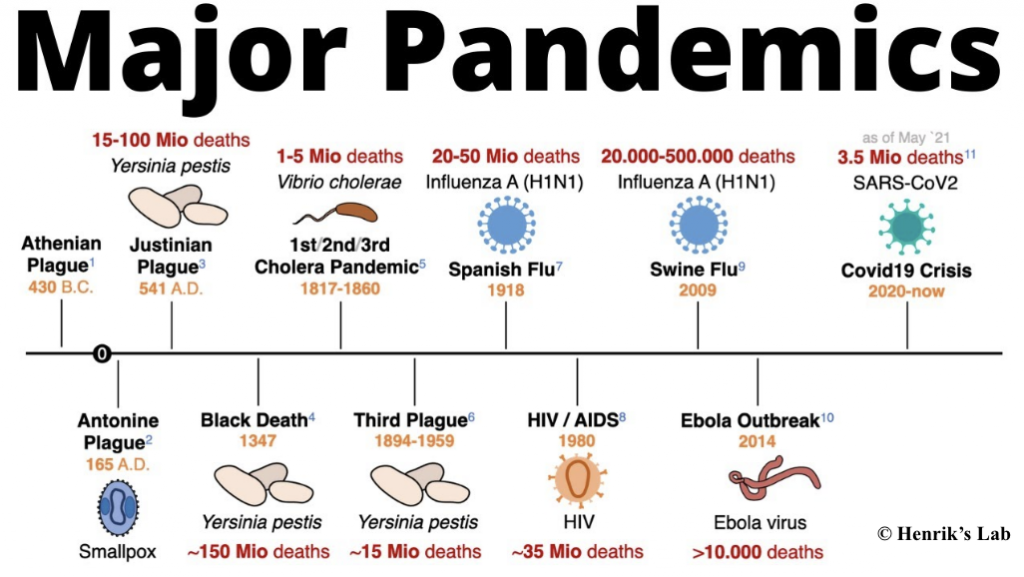

Infectious disease is not a new threat to human populations, but the success of our species in the last few years has been unprecedented. Since the 1800s, the human population has increased tenfold. As a result, urbanisation and population density rates have increased astronomically. With this increasing population, the development of epidemics is ‘accelerated’. In the past thirty years alone, we’ve had at least four viral respiratory pandemics, along with global Zika, Ebola, and HIV outbreaks. Furthermore, these outbreaks are consistently most harmful in densely populated areas. The surge of potentially lethal pathogens that have threatened human survival in recent years has clarified that “epidemics and pandemics seem to be fuelled by human overpopulation and the elicited disruption of the balance between humankind and nature” (National Library of Medicine). In other words: it is not human weakness we have to be most worried about, it is human success.

Moreover, pathogens come in a wide range of forms and abilities. Most pandemics we are familiar with are caused by respiratory viruses: think COVID or the flu. But human overpopulation may have opened the door to a previously unfamiliar and diverse range of biological threats. Fungi, for instance, now poses a “greater threat to human health” due to environmental changes associated with our population growth (CNN). Many different forms of bacteria are adapting to the use of antibiotics, which renders previous treatments ineffective. Contamination of natural sources may even leave us at risk of unknown toxins emitted by hazardous organisms, and human encroachment on previously undisturbed wildlife opens up the possibility that humans will contract zoonotic diseases, both of which pose unique risks to human immunity.

In all likelihood, the next pandemic will not irrevocably endanger the human population. But with the rise of our species’ size, coupled with the pathogenic breeding grounds created by human growth and the startling lack of foresight demonstrated by the international medical community, the possibility is becoming more and more plausible.

Each pandemic provides the opportunity to discern the identity of the pathogen capable of jeopardizing the human species. For a pathogen to inflict the damage necessary to imperil our population, it must have three key characteristics. Firstly, the pathogen must be highly virulent; it must have an incredibly low dosage rate necessary for infection and transmission, such as Ebola or COVID. Typically, the most virulent pathogens are also transmissible before symptoms start to show, in order to effectively reach wider populations. Moreover, the microbe must be ‘environmentally resistant’, a concept used to describe the period of time in which it may survive outside of a potential host. Lastly, but most importantly, the host must not have any innate immunity against the pathogen. As of today, no microbe exists which can fulfill these three requirements in humans, but if it did, as in other species, it is likely that our population would be in severe danger of extinction.

The eradication of the human race in this scenario is not a given, though, due to humanity’s unique abilities, which may be both the cause and the cure for our demise. Staggering medical advancements, for instance, have been made in the last few centuries which have the potential to outpace the evolution of biological dangers and strengthen our defense against pathogenic disease. The introduction of germ theory has dramatically altered our susceptibility and understanding of potential threats. The discovery and distribution of antibiotics and vaccines (along with other antiviral and antibacterial treatments) have revolutionized the field of medicine and provided one of the first possibilities of a cure against hazardous microbes. The study of genetics provides a way forward to understanding our special weaknesses, and the fields of epidemiology and immunology can help predict the challenges we may encounter. The threats we face from nature cannot be ignored, but there is no denying that there is something that sets humankind apart which has kept us alive until now. With any luck, it will continue to do so.

Over a century ago, H. G. Wells published a science fiction novel titled The War of the Worlds, in which Martians attempt to take over planet Earth. The humans try everything to protect their homeland, but by virtue of their technological advancements, the Martians indisputably become the new masters of the planet. At the end of the novel, the Martians’ fates are revealed:

Silent and laid in a row were the Martians— DEAD!—slain by the disease against which their systems were unprepared; slain, after all man’s devices had failed, by the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this earth. For so it had come about, as indeed I and many men might have foreseen had not terror and disaster blinded our minds. These germs of disease have taken the toll of humanity since the beginning of things—taken toll of our pre-human ancestors since life began here. But by virtue of this natural selection of our kind we have developed resisting power; to no germs do we succumb without a struggle. (…) It was inevitable. By the toll of a billion deaths man has bought his birthright of the earth, and it is his against all comers; it would still be his were the Martians ten times as mighty as they are. For neither do men live nor die in vain.

The book’s ending demonstrates how humans belong on this planet, and we have the ability to fight for our place here. But it also reminds us that nature cannot be ignored. Human progress should be celebrated and welcomed, but there may come a point at which, in the natural scheme of things, we resemble the Martian more than the human. So if we want to be ready for the next pandemic, whenever it may come, “we need to get going, because time is not on our side” (TEDx). When it does come, it will not wait – and neither should we.

Bibliography:

Christensen, Jen, and CNN. “The Fungal Threat to Human Health Is Growing in a Warmer,

Wetter, Sicker World.” CNN, 7 Feb. 2023, www.edition.cnn.com/2023/02/07/health/fungus-health-threat-scn/index.html.

Gates, Bill. “How To Prevent the Next Pandemic.” Penguin Books, 21 May 2022.

Gates, Bill. “The next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready.” TED, 3 Apr. 2015,

www.ted.com/talks/bill_gates_the_next_outbreak_we_re_not_ready.

Henrik’s Lab. “Major Pandemics”, Youtube, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rKvnzWhtWQ.

Accessed 7 Oct, 2023

Hogg, Peter. “The Top 10 Medical Advances in History | Proclinical Blogs.” Proclinical,

Proclinical, 21 June 2021, www.proclinical.com/blogs/2021-6/the-top-10-medical-advances-in-history.

LiveScience, and Gholipour Bahar. “What 11 Billion People Mean for Disease Outbreaks.”

Scientific American, 26 Nov. 2013, www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-11-billion-people-mean-disease-outbreaks/.

Osmosis Team. “HealthEd: The Top 10 Medical Advances in History.” Www.osmosis.org, 12

July 2023, www.osmosis.org/blog/2023/07/10/the-top-10-medical-advances-in-history.

Plaue, Noah. “The Greatest Biological Threats to Civilization.” Business Insider, 29 June 2012,

www.businessinsider.com/the-biggest-bioweapon-threats-according-to-the-federation-of-american-scientists-2012-6. Accessed 30 Sep. 2023.

Rogers, Kaleigh. “Why Did the World Shut down for COVID-19 but Not Ebola, SARS or Swine

Flu?” FiveThirtyEight, 14 Apr. 2020, www.fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-did-the-world-shut-down-for-covid-19-but-not-ebola-sars-or-swine-flu/.

Spernovasilis, N., et al. “Epidemics and Pandemics: Is Human Overpopulation the Elephant in

the Room?” Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, vol. 19, Dec. 2021, p. 100728, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8530531/. Accessed 30 Sept. 2023.

Wells, H.G. The War of the Worlds. 1897. Harlow, Essex, England, Pearson Education, 2008, pp. 273–274, www.planetpublish.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/The_War_of_the_Worlds_NT.pdf. Accessed 30 Sept. 2023.