Whatever you think you know about vampires, there is more, and pop culture’s take isn’t nearly as interesting. Vampires aren’t simply bloodsucking undead creatures of the night who can only be killed with a wooden stake through the heart. Despite different cultures having different names for such beings, including the Germanic legend of the nachzehrer, all vampires share a similar essence: someone who has died and come back to life with the sole purpose of feeding on humankind.

Although people today may scoff at the idea of vampires, those of the past had seemingly good reasoning for their beliefs. Nevertheless, modern medicine and an improved understanding of what happens to the body postmortem has negated some of said reasonings. However, until these revolutionary discoveries, vampires rising from their graves proved a common fear; evidence of preventative practices have been found in numerous ‘vampire graves’ across the world, primarily in Europe and the New England region of the United States. To understand the true meaning behind vampires, one must understand the beliefs, actions taken, and the science behind the lore. Dracula may be merely a story, but his origins constitute a significant part of human history.

Stories of creatures rising from the dead to attack the living are recognized around the world, with one of the most well known renditions being the vampire. Despite global recognition, folklore surrounding vampires extends much further than popular culture depicts. One example is the nachzehrer, a shroud-eating vampire which features prominently in Germanic folklore, especially that of Northern Germany; the folklore of neighboring regions including Silesia, Bavaria, and that of the Kashubians of northern Poland holds similar creatures. According to these legends, the nachzehrer must consume both its burial shroud and body in order to survive. Once the nachzehrer has begun consuming its shroud, the deceased’s family members would grow increasingly ill as the nachzehrer “fed on their life force”.

Additionally, those who were believed to be plagued by vampires during the New England Vampire panic of the 1800s also appeared to be being drained of their life force. Although not always called by the same name, vampires spent decades harming the families of New England. As the vampire panic and consequent deaths ensued, action needed to be taken, resulting in situations such as that of Mercy Brown.

In Exeter, Rhode Island, 1882, the Brown family contracted a disease people called ‘consumption’. Within two years, Mercy’s mother and older sister died of the disease, and throughout the duration of it life seemed to drain from their bodies. Around a decade later, Mercy followed suit. Just months after her death, her brother Edwin became sick as well. This is when the townspeople became suspicious that something more sinister had been happening to the Brown family. Lore at the time dictated that when a family contracted disease and began to die off, the family members who had died the earlier deaths were vampires, and were to blame for the subsequent illnesses in the family.

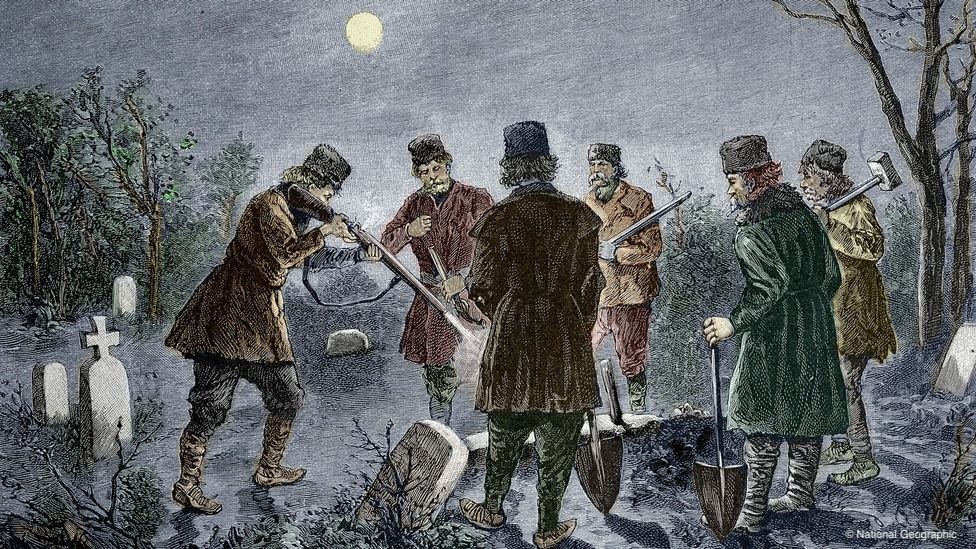

In order to prevent Edwin’s death, Mercy’s father was convinced by his neighbors to let them exhume the bodies of his wife and daughters to check for fresh blood in the heart. This would confirm they were feasting on Edwin’s flesh and blood, causing his illness. The town dug up the three women; the bodies of Mercy’s mother and sister displayed not much more than bone due to their decade-long rest. Mercy’s body, on the other hand, seemed remarkably well preserved. Her heart and liver were removed, and upon examining the heart, blood was found.

Armed with their evidence, the villagers declared Mercy Brown a vampire, and, in order to prevent Mercy from continuing to drain the life from her brother, burned her heart and liver on a rock and used the ashes to concoct a tonic, which Edwin consumed. This, the village believed, would keep him alive. Edwin died just over a month later.

While a tonic made of the vampire’s ashes wasn’t a ‘one-time-only’ incident, there have been many other methods of warding off vampires. Often these methods involved the burial itself, and archeologists have found hundreds of what they believe to be ‘vampire graves’ across the world.

In Poland, bodies have been found with their skulls resting atop their legs in accordance with the old Slavic practice that decreed that decapitated vampires could not come back to harm the living. Other Slavic bodies have been found with sickles across their throats, so that if the vampire tried to sit up in the grave it would decapitate itself. Additionally, prior to the conversion to Christianity, Slavs cremated bodies in order to allow the person to “fully” pass on and prevent them from becoming a vampire.

Then, on the Greek island Lesbos a body was found buried in a heavy wooden coffin, with several long iron spikes driven through its neck, pelvis, and ankle. The iron spikes on their own prompt the possibility of a vampire burial; however, seeing as the rest of the bodies in that cemetery were buried solely in a cloth shroud, very little doubt remains that whoever buried this person under no circumstances wanted the buried to be able to escape their grave.

Moreover, in 2006, a woman was unearthed among medieval plague victims with a brick lodged in her jaw, which used to be a common anti-vampiric practice in Italy. Similar bodies have been found, and it is theorized that this was likely due to the belief that it would prevent the corpse from eating its way out of the grave. More recently, the body of a child no older than six was found face down in its grave with its big toe padlocked in order to prevent the child from ascending to haunt the living in case it came back to life as a vampire. Nearby, the body of a woman was found with her toe padlocked as well, and an iron sickle over her throat. Near the end of the middle ages, using a padlock to keep potential vampires in their graves became almost a custom, especially in the Jewish communities in Poland. Of the 1,200 graves investigated by archeologists in Lutomiersk, a town in central Poland, about one third contained padlocks.

Credit: CB2/ZOB/WENN.COM/NEWSCOM via National Geographic

The most important question, of course, is why? Why were so many people suspected of being vampires? Ultimately, not knowing how the body decomposes may have been a significant influence. In the weeks and months following death the body decomposes, and the stomach releases a dark liquid called purge fluid which can easily be mistaken for blood and may flow from the nose and mouth. This could give the impression that the individual in question has recently feasted on the blood of the living. Sometimes, this fluid would moisten the burial shroud near the deceased’s mouth, making it sag and/or tear, creating the appearance that the body was eating the cloth, such as in the legends of the nachzehrer. When it comes to the belief that the nachzehrer ate its own body, this was likely due to natural scavengers, which, in all likelihood, people didn’t see or weren’t aware of.

As for the remarkably well-preserved state of Mercy Brown, a New England winter will quite easily slow the speed of decomposition. Furthermore, the ‘consumption’ disease, as it was once called, is now known as tuberculosis. In fact, the majority of the major New England vampire scares occurred in accordance with tuberculosis epidemics, which likely influenced and encouraged the scares themselves. Death from tuberculosis fed the idea of a vampire being responsible, as it often plagued a person for years, slowly and visibly wasting away the body, truly giving the impression that the person was being drained of their life.

Today, medical practitioners understand death and disease to a much greater degree than during the 1890s. Doctors have a lot of knowledge around, and are able to treat, tuberculosis in a way that just was not possible during the vampire scares. Though the disease was identified in 1882, tuberculosis lacked any sort of drug treatment until the 1940s; even then, the knowledge wasn’t widespread enough for doctoral advice to prevent much during the scares.

So, vampires. Not exactly the charming and often aristocratic people living in castles with the unfortunate urge to drink human blood one would expect. There is a lot more history involved in these legends than popular media depicts. Vampires have become icons in mass culture, and a joke, in many ways. But for a long time, people genuinely feared their deceased family members were waking up in their graves. Hundreds of people had their bodies desecrated, or “trapped” in their graves because their family thought they might be undead, murderous creatures. If you asked the people of Exeter in 1892 what was killing the Brown family they’d say it was a vampire. They would tell you Mercy Brown came back from the dead and was haunting her living family. Even today, with the full extent of knowledge and scientific evidence there is to largely nullify vampire claims, people still remember her as the vampire that killed her family. Mercy Brown was nineteen years old when she died a long, painful death, and she has since been immortalized as nothing more than a monster. A vampire.

Bibliography:

Tucker, Abigail. “The Great New England Vampire Panic.” Smithsonian Magazine, Oct. 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-new-england-vampire-panic-36482878/ Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Pringle, Heather. “Archaeologists Suspect Vampire Burial; An Undead Primer.” National Geographic, 16 Jul. 2013, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/130715-vampire-archaeology-burial-exorcism-anthropology-grave Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Ingber, Sasha. “The Bloody Truth About Serbia’s Vampire”, National Geographic, 17 Dec. 2012, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/121217-vampire-serbia-supernatural-garlic-fangs-science-weird Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Dell’Amore, Christine. “‘Vampire of Venice’ Unmasked: Plague Victim & Witch?” National Geographic, 27 Feb, 2010, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/100226-vampires-venice-plague-skull-witches Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Lidz, Franz. “Undying Dread: A 400-Year-Old Corpse, Locked to Its Grave.” New York Times, 5 Sept. 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/05/science/archaeology-burial-vampires-revenants.html Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Rapp Learn, Joshua. “Burials Unearthed in Poland Open the Casket on The Secret Lives of Vampires.” Smithsonian Magazine, 27 Oct. 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/deviant-burials-poland-open-casket-secret-lives-vampires-180966970/ Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Staff, Ancient Origins. “Nachzehrers: The Shroud Eating Vampires of Germanic Folklore.” Ancient Origins, 1 Jun. 2016, https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/nachzehrers-shroud-eating-vampires-germanic-folklore-006010 Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Levy, Daniel S. “Tracing the blood-curdling origins of vampires, zombies, and werewolves.” 25 Oct. 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/tracing-the-origins-of-vampires-zombies-and-werewolves Accessed 30 Sept. 2023

Urbiola, Oscar. “How did 18th-century vampire hunters identify the undead? Blood and fingernails.” National Geographic, 29 Oct. 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/vampire-mania-in-eastern-europe Accessed 30 Sept. 2023